Deducing the Problem With Detective Games

How do you make the player feel like a genius when your game's narrative depends on their progression?

Written by Boofybaps (@boofybaps)

Detective TV shows, books, and movies are timelessly prominent and relevant, with characters like Sherlock Holmes lasting centuries and shows like Law & Order running for decades. So then, why has one of the most popular story genres struggled to make a similar impact in video games? Does the genre fail to attract investors and customers, or is it inherently challenging to translate into gaming? I will not rest until I get to feel like Lieutenant Columbo, so let’s get to the bottom of this.

Case: The Genre Itself

Certain storytelling genres excel as video games. Fantasy, Action, Sci-fi, and horror are clear examples, as their core storytelling tenets translate well into an interactive medium. Genres imbued with superhuman abilities, enemies, monsters, and physical danger mesh well with the simple, well-defined mechanics of combat and movement. There are only so many games that feature regular people with average skills struggling with day-to-day problems with much meaningful interactivity in the gameplay. The stories exist in the medium but are often regulated to visual novels and the like.

So, how does the Detective story fit into this space? The skills are above average, and the problems are far from mundane, but a detective’s only important tools are their brain and their senses. Surely, a detective game can feature a punch button, but you won’t uncover who killed who by punching everyone you see. The detective must enter a crime scene, seek clues, interview people, discern truth from lies, and then piece everything together. The developers’ job is to find a way to reward those actions.

The developer immediately runs into a problem when making this kind of game: what if the player cannot deduce things on their own? An action game can have the player try again and again until they master the button sequences necessary to complete the challenge. The detective game struggles here as any interesting detective story requires the detective to be an innovative thinker who sees past what the aloof police officers take for granted, if not an outright genius.

Every Detective story is actually two stories: the crime and the investigation. Detective games that struggle to be impactful put too much focus on the story of the investigation. Games with detective protagonists, a plot structure, and their own pacing in mind often sacrifice a satisfying deductive challenge in favor of the story’s flow. However, without giving the player any narrative or artificial reward for their successes in the investigation, the game feels hollow. A reward system must be in place, but narrative progression is toxic for detective gameplay.

Exhibit A: Call of Cthulhu

Call of Cthulhu is a Lovecraftian detective game based on a board game of the same name. After introducing our divorced alcoholic detective protagonist, we are dropped off on a dark, spooky fishing island with no direction besides a single name to find. It was exciting to arrive at a game that felt so open. A civilian you interview tells you about a warehouse the murdered couple owned. A pop-up prompt decides you need to investigate there despite Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum blocking the entrance.

From here, you have a few options: an eloquence roll to talk them into moving, a strength roll to threaten them into moving, or if you speak to enough people, you’ll learn information about their boss and use insider knowledge to trick them into moving. Here, it seems like I have a few choices, and the only one guaranteed is the one that requires investigation. Regardless of how you do it, you are caught, thrown out immediately, and told to go to the next plot point. The benefit of your investigation and trickery was not furthering your investigation but furthering the story.

It becomes clear the openness is a facade hiding an utterly linear experience with an occasional lock-and-key puzzle blocking story progress. The player doesn’t make any true deductions for anything but short, simple issues like finding a way to distract guards or knock down walls. It does not feel like I am solving the case. It feels like I’m doing chores for the real detective while he thinks about the hard stuff.

The issue with Call of Cthulhu and similar games like Observer is that they have a narrative progression that must flow smoothly. They cannot risk the narrative payoffs for the sake of player freedom, but limiting that freedom disconnects the player from the protagonist. Without agency over my participation, I am merely doing chores. The protagonist gets to solve a case and go on an adventure while I sneak around and find clues for them. Sitting back and watching someone else solve a case while helping a bit here and there leaves me feeling much more like Watson than Sherlock.

Exhibit B: Her Story

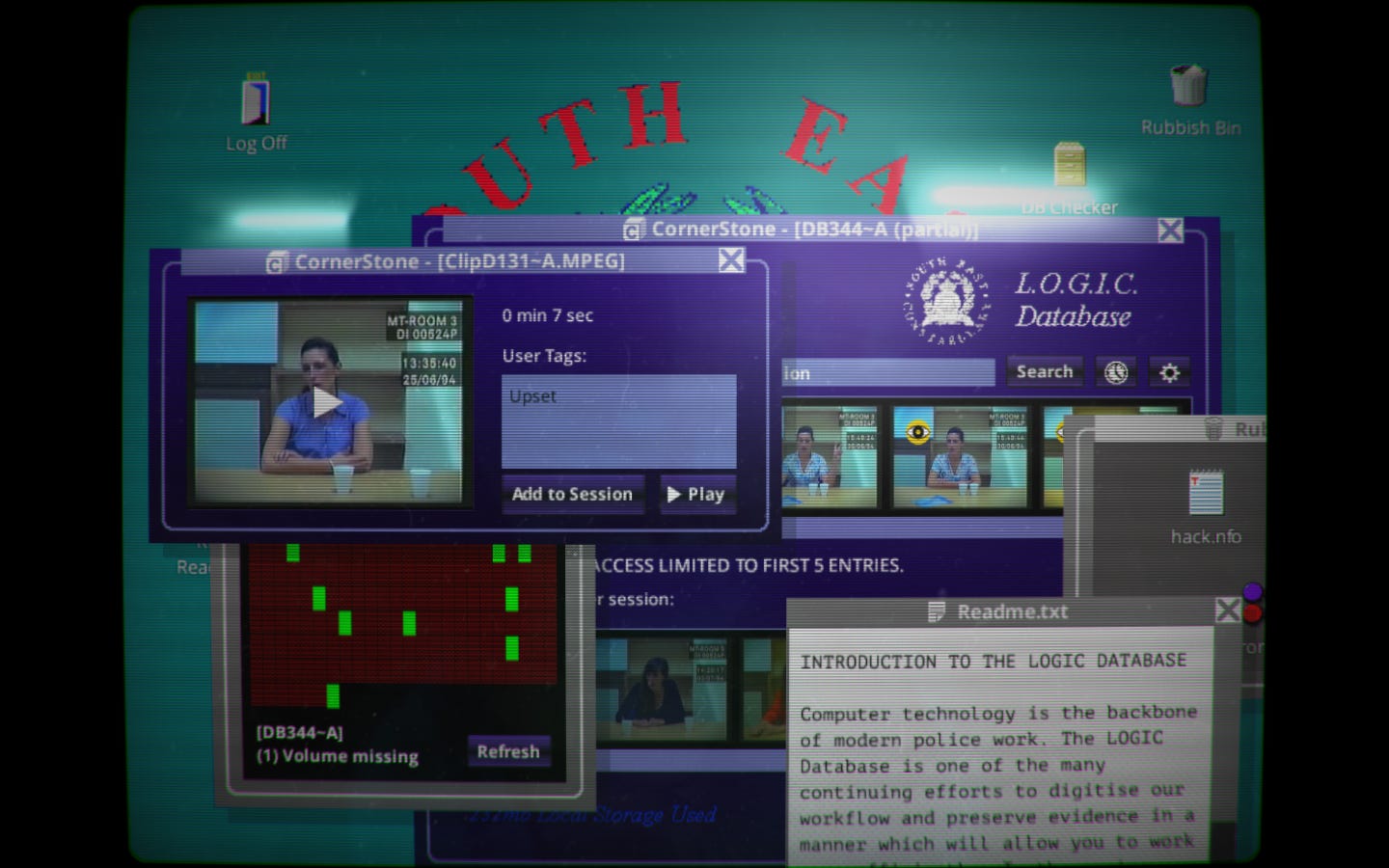

An example of detective gameplay that struggles in a completely different way is Sam Barlow’s unique Her Story, a deposition software murder mystery I like but couldn’t love. The player is put in front of software that gives the ability to type keywords to find clips of a murder suspect’s deposition footage, and that is all. There is no narrative taking place during the unraveling. There are no cutscenes or character growth. You only ever see the player character in occasional reflection shots on the screen of their computer. I found it effective as I filled out notebook pages of connections, knock codes, and keywords to test.

There is also no instruction or interruption by the game itself. You’re put in front of this program and left alone to watch videos and piece together a fascinating narrative by an unreliable narrator piece by piece. It has no reward artifice to satisfy you or prove your progress. There is nothing within the system of Her Story that says you are successful. There is no reward when you get to see the actual murder through CCTV because you accurately diagnosed her with the correct mental disorder. After you’ve watched a satisfactory percentage of the videos, a chat window pops up and says “You done?” at which point you can just answer yes to get credits. You only stop playing when you’re personally satisfied with your knowledge of the story.

The game doesn’t have to invent a reward; it creates a situation where you are personally motivated by your interest in the story, and the reward is when you get what you sought. On the one hand, we should celebrate such a pure and unique look at how we can motivate the player to become a detective. On the other hand, Her Story ends on a dull note, with the player eventually losing interest in the game. There is an exciting feeling when it all clicks, but you only have to watch about thirty percent of the content for it to make sense. Then you’re left with a massive pile of videos and Steam achievements you’ll have no issue walking away from. It was unique and innovative, but the limitations lessened the impact and stopped me from truly loving it.

Her Story presents the necessity of some artifice, while Call of Cthulhu cautions against an excess of it. When the biggest deductive challenges are handled in cutscenes, it disconnects us from the satisfaction of overcoming them. When the game cannot reward you with anything more than the joy of the solution, it loses what makes games memorable and impactful in the first place. At the end of these experiences, I was left thinking, “This might as well have been a movie.” The issues inherently stem from the games’ lack of meaningful interactivity.

Expert Testimony: The Successes

The time has come for me to mention the notable successes, lest I be accused of straw-manning an entire genre with its weakest entries. L.A. Noire, The Wolf Among Us, and Ace Attorney are all games that have seen financial and critical success. These games unequivocally feature a detective main character who investigates murders to bring justice. However, despite their accomplishments, I don’t think they are free from the issues I’ve discussed.

L.A. Noire is likely the highest regarded and budgeted straight-edge detective-y detective game in existence, with the public consensus of it being “pretty good!” As Detective Cole Phelps, you collect evidence, use it strategically in interrogations, and solve cases. It is likely the first game that pops into the average person’s head when detective games are mentioned. Despite containing the mechanics and writings of a quality deductive experience, the game is far from perfect. It is possible to fail every deductive challenge and still play through the entire game’s story. The linear narrative rears its ugly head again to necessitate freedom from difficulty. To keep the player entertained, every case has a backup scenario that automatically unfolds if you cannot figure out the case on your own.

The Wolf Among Us is a choice-based telltale adventure game wearing the skin of the fantasy detective comic-book series Fables. I had one playthrough where I decided to be the worst detective ever. I chose the meanest options, never asked questions, and even killed the main bad guy before they could explain what their plan and motivation were. The game’s story hardly changed at all and hardly required any deductive reasoning outside of the occasional point-and-click key-hunting challenge.

I appreciate that Ace Attorney games will fail you and start you over if you don’t solve the case. Sure, some of the same problems come with a linear narrative, but the game demands you to be a good detective to get there. The only problem with Ace Attorney is the difficulty. Everything is often spelled out and obvious, with many hints worked into the dialogue, and often, deduction isn’t as necessary as attentiveness. They are very light, casual games that make for enjoyable tea-time fun. I enjoy them but do not go to them for a deductive challenge.

Also, for those screaming, “What about Disco Elysium?” I’ll say this: While Disco Elysium is absolutely a game about a detective solving a murder, the appeal of that game is not in the deductive reasoning, especially considering halfway through the game, the murderer just admits it to the player. I love Disco Elysium for its philosophical, hilarious writing, the atmosphere, and for providing the experience of being a character in a strange Russian novel, but not for deductive puzzles. While yes it is a game about a detective who solves a case, I’d use many other words to describe it before I called it a detective game.

Case Closed?

The games about Investigation and Deduction I love the most rarely feature a linear narrative about a detective solving cases. Return of the Obra Dinn and Curse of the Golden Idol are amazing ways to explore deduction gameplay that is impactful, fun, and unique. Still, the player is an outsider unfolding the story. Also, Shadows of Doubt may be the greatest detective game ever created that perfectly gamifies the rewards for solving cases, but that’s such a big topic it would require an article all its own.

I want more detective games. I think it’s a type of fun that is perfect for the medium, and I want to see more developers attempt it. Hopefully, they avoid these pitfalls and make intelligent, challenging experiences that only games can. If they don’t, I will have to go back to stalking crime scenes and solving cases in the shadows even though the judge told me to stop. “Sorry, your honor, it’s either this or undergoing a lobotomy to play Return of the Obra Dinn for the first time again.”